In the late '90s, I had a colleague who was fond of saying, “When an operations analyst encounters a problem, he opens a spreadsheet. Now he has two problems…”

Indeed.

If you are responsible for a project that has a spreadsheet as a deliverable, go and suspend it now. Yes, now. Go on. When you return I'll explain why you had to do it.

Done? OK, I'll continue.

First, let me change tack for a moment. I'm actually a big fan of spreadsheets. I use them regularly. Excel is a great application. However…

spreadsheets should not be used for "line of business" applications.

In fact, I'd go further:

spreadsheets should only be used by the person who created them.

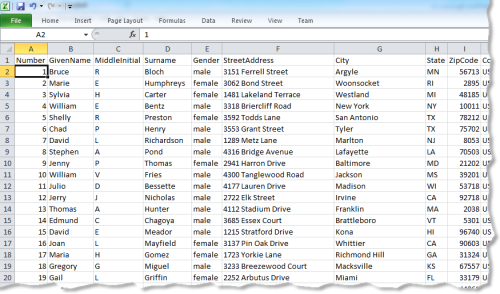

And, sometimes, not even then. We've all seen spreadsheets like the one below.

This isn't a spreadsheet. It's a database. And there are applications designed specifically to handle this sort of data. They're called "databases".

The "spreadsheet as database" is a pet peeve of mine as I receive data in this format all the time—and it's always a major pain. Consistency is hard to maintain when storing data in spreadsheets. You end up with customer IDs in the "Orders" sheet that can't be found in the "Customers” sheet. Or a sales tax of "Smith". A particularly pernicious problem with using spreadsheets in this manner is their tendency to autoformat fields. If I had a dime for every time a numeric customer ID with leading zeros had been formatted as 6.72512E+11…or an order had been fulfilled during the reign of Queen Victoria…

Also, there's a significant risk of messing up your data when it's held in a spreadsheet. Miss the fact that a sort hasn't included all of your columns and your records could be rendered worthless.

Even if you're maintaining a small database for your own use there are more appropriate solutions than using a spreadsheet. You don't have to become an Oracle database administrator. Personal database products like Bento are as easy to use as a spreadsheet. If you have a spreadsheet "database" in a corporate setting, and it's doing more than managing your lottery syndicate, then someone needs to be fired.

So, OK, it's not a good idea to use a spreadsheet in place of a database. But, spreadsheets are perfect for managing your accounts, right? Columns of numbers, balances, etc. Ideal.

Well, not really. The problem is that there are all sorts of rules and structure that can be used to help you manage your accounting—and spreadsheets don't utilize any of them out of the box. A specialized accounting application will check that accounts balance, report outstanding invoices/bills, calculate taxes, etc. You can build some of these features into a spreadsheet, but why do that when the work has already been done by experts? Also, no-one is going to be au fait with your custom spreadsheet, so when it comes time to share the accounts with a colleague, or your accountant, there's scope for confusion and mistakes. If you use a professional accounting package, however, it will have a structure that is familiar to anyone who has experience of business accounting.

Another problem with the use of spreadsheets in accounting is accuracy—a problem that will pop up again and again in this article. It is all too easy for a newly added row not to be included in a summation formula. Or for a tax rate to be changed inconsistently.

Unless your spreadsheet is being used by your lemonade stand business to see if you can afford that hamster, buy Quickbooks.

This seems like an appropriate point to address, in more detail, the lack of accuracy in spreadsheets. Sarbanes-Oxley and similar laws have resulted in more scrutiny of financial planning systems—and consequently, more scrutiny of corporate spreadsheets. Research, such as that reported by Raymond Panko in "What We Know About Spreadsheet Errors", has found that most of the spreadsheets used by organizations contain errors—and that a considerable number of those errors are serious. In one case reported in Panko's research, the error would have caused a discrepancy of more than a billion dollars! Similarly, an article by Mark Ward in New Scientist reported that Coopers & Lybrand found errors in 90% of spreadsheets they audited. Finally, the European Spreadsheet Risks Interest Group maintains a list of horror stories about real-world losses due to spreadsheet errors. Don't read it with the lights off.

Why are there so many errors in spreadsheets? To be fair, spreadsheets aren't the only models that contain errors. We all know that software has its fair share of bugs. But the sheer number of spreadsheets, coupled with their "homespun" development, and the difficult of reviewing their logic, makes spreadsheet development the Wild West of the modeling community.

It's extremely difficult to develop accurate spreadsheet models. Professional software developers liken it to programming in ancient languages that rely on the notorious "goto" statement. And then there's the challenge of reviewing formulae that contain "variables" such as "JG271". Paradoxically, familiarity with spreadsheets encourages inexperienced developers to "have a go". While I applaud this adventurous spirit, it doesn't result in well-crafted models.

The software development community has invested extensively in languages, frameworks and tools to improve the quality of software. In comparison, relatively little work has been done to improve the quality of spreadsheet modeling—and the work that has been done has had minimal impact on spreadsheet users. People find it difficult to maintain an understanding of complex logic, so they need to break large models down into simpler components. This isn't as easy to do in a spreadsheet as in, say, a modern object-oriented programming language.

Spreadsheets become increasing complex when models contain conditional (if X then Y else Z) and looping (do X Y times) logic. All business analysts will have encountered Monte Carlo spreadsheets that had thousands of rows of automatically generated results—and involved lookup logic for using those results. Macros can be written to address some of the challenges of using spreadsheets, but extensive use of macros is a clear indication that a spreadsheet may not be the best platform for your modeling. You end up dealing with all the complexity of software development, but suffering the weaknesses of spreadsheets for your efforts.

It's also all too easy to enter bad data into spreadsheets. A wrong keystroke and a formula is replaced with a static value, rendering the calculations meaningless. Freeform data entry allows you to destroy a model in an instant. Protected cells can only do so much. And, once again, if you protect entire sheets and have users interact with the data exclusively through macros, you're not exploiting the native strengths of the spreadsheet platform in the first place.

Another (ab)use of spreadsheets that I'm compelled to address is their use in business models—strategic planning models, forecasts, simulations, what-if analyses, etc. These models tend to have an extended lifespan, over which they are "tweaked" extensively—by different analysts—and used as the basis for significant corporate decisions. These are probably the most challenge models of all to develop—and, therefore, the most prone to errors.

Consider this: how many business problems are actually a natural fit for a two- or three-dimensional grid of cells? The gap between the real-world and the modeling environment is known as the "impedance mismatch"—and, in spreadsheet modeling, it's generally huge. The gap is generally smaller when a modern programming language is employed, as the software designer can map objects to real-world entities. Higher impedance mismatches place higher demands on the analyst, in terms of understanding the model. So, when dealing with an unfamiliar model—either due to its being a while since the model was used, or because it was originally developed by someone else—the chances of mistakes being made are correlated with the impedance mismatch.

If you are building a business model, use a specialist tool (e.g. a simulation application) or a general purpose programming language. That "little spreadsheet model someone threw together in a few days" will eventually cost you dearly.

Hold on? If spreadsheets are so bad at everything, should we be using them at all?!

Who said they were bad at everything? Certainly not me. I'd even go so far as to paraphrase the NRA and say that spreadsheets don't create bad models—people create bad models. And spreadsheets are actually excellent for one very important business activity—prototyping. Prototyping is when you build a model for the purposes of exploring an idea. Or for checking a theory. It basically building a model that you'll discard once you have your answer. Prototypes have a short lifespan and are only used by (or in collaboration with) the original author. They are never used in production.

Spreadsheets excel (no pun intended) in this activity. They are very inclusive, as everyone knows how to use them. And because a lot of thinking about the process they are being used to study is going on, mistakes are less likely to have grave consequences. They can also form the design specification for a more formal model, as the subsequent development process should place more rigorous checks on the logic.

In fact, one wag suggested that spreadsheets would be used more effectively if the save function were removed. I have some sympathy…

OK. I'm guilty of having been a little provocative in this article. But, only a little. If you are using spreadsheets for anything more than individual prototyping in your organization I urge you to seriously consider replacing them with more suitable models.

Porting your spreadsheets to a modern programming language, for example, will:

- result in a design that is a more natural fit to the real-world problem, and, therefore, produce a more accurate model

- allow the use of standard testing tools to improve the quality of the implementation

- allow the use of source code control systems to manage on-going development

There's a stack of evidence that suggests your spreadsheet models are ticking time-bombs.

Please, don't "solve" one problem by making it into two.